Monday, June 9th

9/30

From the meditations of The Pale Metaphysician

Note on programming: apologies for the delay today, to call it hectic would be an understatement.

Yesterday I discussed speed.1 There’s much to say about it. For instance, to get immediately self-referential, the very act of typing out this article digitally is an expression of upmost speed — instant communication. Typing is after all faster than writing. In fact, back in the day I would make a point of writing out the first draft of my articles or papers or essays by hand, purely by hand, to feel the words come out of me. It forced me to slow down even if I wanted nothing more than to expel the ink onto the page in as rapid a fashion as my motor functions would allow.2 If speed is slow-motion suicide, then lethargy must be life affirming! When so much of contemporary existence is marked by efforts to reduce the time between events as much as possible, e.g., text over mail, streaming over cable, scrolling over feeling, the thought is given more credence; indeed, there’s an entire ecosystem of “mindfulness” revolving around slowing down to more fully enjoy life’s splendor.3

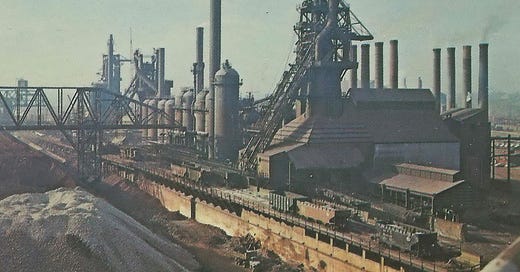

This deserves some additional attention. Technological progression has recently in the grand scale of history been interpreted in some ways as the acceleration of, well, everything: faster communication, transportation, interpretation, integration, a million other “-ations,” all with the promise of greater luxury and comfort. Productivity especially became a focus of speed. The more a laborer can get done in an hour the more value they create (to be exploited …), so goes the logic, though initially there were anxieties over what would be done with the additional free time. Instead, workers were just given more work;—forsooth, we have arrived!

This non-correlation between productivity and leisure which defies the senses lies at the heart of one of capitalism’s damning contradictions, for one must consider “leisure for who?” I answer: the bourgeoisie. Increased speed is one of the many contemporary luxuries afforded to the rentier class — everything from private jets to remote work. What makes this contradiction metaphysically, dialectically damning (remember, I’m not here to idly proselytize) is the falling rate of profit. Glossing over the messier details, the idea is that if value is determined by the labor put into a good or service, and the amount of labor required for a good or service falls as the methods of producing said good or service become more efficient, then one would expect the profit available from that good or service to contract in the long-term. This is, naturally, hotly debated. Obviously if one looks around then it seems profit has decidedly not fallen, but there are countervailing forces putting wind in the capitalist’s sails, of which there’s a few identified by economists far more talented than I; for the purposes here the most important one is that with which I ended the previous paragraph: just give the workers more work. Simple as. Remember that the next time you’re asked to stay late to accomplish another task …

The slow-motion suicide immanent to labor is commonly seen (see: working yourself into an early grave), but another aspect of it at play here is the derealization of the mover. No concept better encapsulates this than alienation, itself also tied to labor. As the worker is further and further removed from the fruits of their labor, as the weight of exploitation bears down heavier, the more they become disconnected from society itself, retreating into their own little bubble. Is it any surprise that the hermit economy is booming in today’s post-COVID, more online, faster world? Here we see yet another slow-motion suicide: that of fading away. Life without living. Empty comfort. Ennui. This existential consequence of speed is nefarious insofar that the act of going real fast is oftentimes its own goal, speed for the sake of speed, and when that blur is finally achieved you cannot stop to look around as you risk losing the raison d’être of your motion.

Repeating trite commentary, contemporary life has sometimes been compared to a conveyer belt in a factory such that one is burdened with so many expectations from the moment one is born that there’s little room for hesitation, for slowing down. Primary, secondary, tertiary education, working, settling down, family, and so on and so on.4 Slowness itself becomes equated with risking missing out on a better life, and nowhere is this better seen than the interview expectations of lucrative fields like tech and finance where the process can start years before the first day on the job, or the hesitation of many to take a gap-year even if it would offer them a chance to figure out how they wish to live their life. Where does it end, this speedy pursuit? If it wasn’t already clear, in a grave — physical or otherwise. It doesn’t have to be this way, though, as there always exists the potentiality of slowing down, of recognizing the processes pushing us in this or that direction and embracing them, or creating one’s own, an exultation of difference in the face of overwhelming quickness. And, as I will explicate in part three of this thrilling series, is not necessarily a global phenomenon.

Additional note: some of you dedicated readers suggest ed to me privately that E. Trabitz has, in fact, sped down highways, to which I reply, “never proven”.

Additionally I believe that the physicality of spilled ink encodes more communicative information than virtual methods, an analog immediacy to speech-acts, but that’s a topic for another time.

I even touched on the idea in an older article, though perhaps with less vampiric language.

I reject the dread oft associated with such notions of being shuttled along in life as having such predictability is a privilege. Furthermore, we choose such paths, inasmuch we possess at least the illusion of free-will. Do we really choose it then? What is choice?

real